By Greg Blood

It is worthwhile revisiting the Olympic Athlete Program (OAP) and Paralympic Preparation Program (PPP) with the strong likelihood of Brisbane and South East Queensland hosting the 2032 Summer Olympics and Paralympics.

These Australian Government funding programs led to Australia having its most successful Summer Olympics and Paralympics to date. Besides the Australia’s high medal count – Olympics (4th on medal table – 58 medals in 20 sports including 16 gold) / Paralympics (1st on medal table – 149 medal in 10 sports including 63 gold), these programs significantly professionalised high-performance sport. The impact of these programs flowed onto successful Australian teams at the 2004 Summer Olympics and Paralympics. Appendix 1 lists medal tallies from 1996 to 2016.

Equally significant, the programs operated with an aspirational can do attitude that allowed athletes, coaches, scientists and administrators to be bold and dare to dream. The programs were dynamic, nimble and accountable and were the catalyst for a unique period of solidarity throughout the network.

The 2000-2001 ASC Annual report on the OAP/PPP stated that “it is appropriate to note its positive long-term impact on NSO’s which developed over the six years of this program’s funding. The improvement in the quality of Australian sport in relation to high-performance planning processes, infrastructure, coaching, sports science and sports medicine personnel; and confidence on the world stage, has been well documented in the international media.”

Background

In September 1992, the Keating Australian Government through Sport Minister Ros Kelly launched its ‘Maintain the Momentum Sports Policy 1992-96‘ which provided $293 million over four years. This funding after the Barcelona Olympics and Paralympics was recognition that increased Australian Government funding resulted in improved Olympic and Paralympic Games results

After winning the right to host 2000 Olympics and Paralympics in Sydney in September 1993, the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) released its ‘Gold Medal Plan‘ in October 1993 that was costed at $437 million over seven years, including participation at the 1996 and 2000 Olympics. The Plan’s aim was for Australia to be ranked in the top five of nations in terms of total medals and gold medals and to send a team of 651 athletes. The AOC followed up its Plan with a Gold Medal Forum in October 1993 that led to a “unity of purpose” amongst the partners in the eventual OAP – they were ASC/AIS, AOC, APC, the State Institutes, the NSOs. They all committed to the objective of success in Sydney across all sports.

In November 1994, the Keating Australian Government in response to a submission from Sport Minister Senator John Faulkner announced ‘Olympic Athlete Program‘ (OAP) which provided an additional $135 million (ended up at $140 million) over six years to prepare Australian athletes for Sydney 2000. The submission was prepared by the ASC and its board. The AOC committed a further $52 million for athlete preparation. his successful lobbying role in the establishment of the OAP and its funding.

Philosophy

The OAP/PPP philosophy was “athlete centred, coach driven and performance based”.

Objectives

- Involvement – to facilitate the preparation of the largest possible Australian team, comprising over 600 athletes so that they may compete to the best of their ability in Sydney in 2000.

- Achievement – for Australia to finish in the top five nations at the Sydney Olympics.

- Legacy – to provide lasting benefits to sport in Australia.

You will see that OAP predominantly focussed on Olympic outcomes.

Management

Olympic Athlete Program Management Committee was established to set directions, develop budget parameters and monitor progress and results. Committee comprised two representatives from the Australian Sports Commission (ASC), Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) and State Institute/Academy of Sport (SIS/SAS) and chaired and serviced by ASC through its Sport Management Section led by Geoff Strang.

OAP Boards were established in 13 Olympic sports to oversee their elite programs and use of funds. OAP Review Committees were set up for other Olympic sports and these comprised representatives from the AIS, the high-performance manager and national coach of each sport and regularly reviewed their high-performance programs.

The management of the OAP represented a significant paradigm shift in managing elite sports performance. OAP for the first time in Australia led to all elements of a national sports organisations high-performance program being fully scrutinised. This required greater accountability, cooperation and synergy between all service providers (AIS, AOC, SIS/SAS, sports science/medicine providers etc). This approach led to several high-performance programs being centralised much to the dismay of several SIS/SAS and high involvement of the ASC in managing several high performance programs.

Olympic Athlete Program Management Committee members had periods of disagreement in terms of direction of resources and this can be attributed to their different objectives.

Sport Categorisation

Sports were categorised in their likelihood of medal success and funding was distributed based on this categorisation. Several sports – archery and taekwondo moved up categories due to improved international performances.

An important underlying principle was that all disciplines of all sport were provided with financial support and the opportunity to evolve and perform in Sydney.

Category One (High potential for success) – Athletics, Basketball (Men & Women), Canoeing, Cycling, Hockey (Men & Women), Rowing, Shooting, Softball, Swimming, Triathlon, Water Polo (Women) .

Category Two (Prospects for success) – Archery, Baseball, Diving, Equestrian, Football, Gymnastics, Taekwondo, Tennis, Volleyball (indoor and beach), Water Polo (Men).

Category Three (Little chance of success) – Boxing, Fencing, Handball, Judo, Modern Pentathlon, Synchronised Swimming, Weightlifting, Wrestling.

Funding Distribution

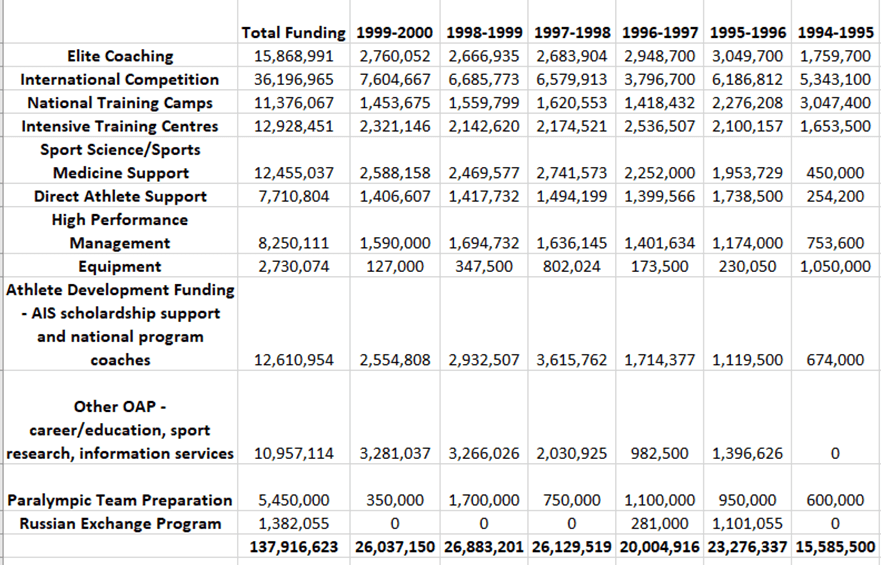

Table One – Funding by OAP Priorities

Table 2 – Funding to National Sports Organisations 1994/95 – 2000/01

Funding to 2000/01 is included as it highlights reduced funding to NSO’s post 2000 Games.

Progression of OAP/PPP

1994-1996 Funding Period

- All Olympic sports with increased funding including those with previous limited international success ie handball, fencing, table tennis.

- Established high-performance management programs for each sport. All sports had employed either full-time or part-time high-performance managers to work with national coaches in developing and implementing elite athlete programs.

- Focussed on the preparation of athletes and teams vying for selection in the 1996 Olympics.

- Six sports established ITC programs using OAP funds. OAP was used to employ elite coaches. SIS/SAS funded other program costs.

- Sports science/sports medicine network established in cooperation with SIS/SAS. Sports Science/Sports Medicine Coordinators appointed full or part-time in 11 Olympic sports.

- OAP provided funding for athletes to attend two major international events in 1995-1996.

1997-2000 Funding Period

- OAP Review led to increased funding to sports with greater prospects of medal success.

- In 2000, it supported 827 Olympic athletes in 33 sports programs and 302 Paralympic athletes in 18 sports. Generally the OAP/PPP supported the number of athletes likely to be selected for a sport at the Games plus 50 percent. The Olympic team ended by comprising 617 athletes.

- OAP funding established AIS programs in Canberra for boxing, archery, shooting, women’s football and wrestling.

- AIS men’s and women’s indoor volleyball transferred to AIS in Canberra.

- Assisted funding some Sydney Olympic test events that provided athletes and coaches the ability to familiarise themselves with Sydney Games facilities in a full competition environment.

Reviews

- Review of OAP/PPP in Dec 1996 (post 1996 Atlanta Games) – evaluation involved the assessment of each sport’s international level performance, with the outcome of the review determining funding for the next two financial years.

- Second OAP Review in April 1998 refining high-performance programs and further targeting athletes/teams with best prospects of success. PPP sports developed plans through to 2000.

Program Foundations

Elite Coaching – $15,868, 991 (1994-2000)

This involved funds for the recruitment, both within Australia and overseas of highly skilled and experienced national head coaches in summer Olympic sports. Overseas appointments included Victor Kovalenko (sailing), Bodo Andreas (boxing), Richard Fox (slalom canoeing), Istvan Gorgenyi (women’s water polo), Ki Sik Lee (archery), Brad Saindon (women’s volleyball), Stelio DeRocco (men’s volleyball) and Vladimir Galiabovitch (shooting). It should be noted that prior to the OAP, the AIS had a strong history of appointing highly credentialled overseas coaches such as Reinhold Batschi (rowing), Ju Ping Tian (gymnastics), Dennis Pursley (swimming), Heiko Salzedel (road cycling) and Gennadi Touretski (swimming). (List of overseas coaches)

International Competition – $36,196,965 (1994-2000)

OAP squad athletes were generally provided funding to compete at a major international events per year based on their sports categorisation: category one = 3 trips, category two = 2 trips and category three – 1 trip.

The increase in international competition opportunities in 1995-96 saw many athletes achieve Olympic qualifying standards and resulted in the largest Australian Olympic team at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

Intensive Training Centres (ITC) – $12,928,451 (1994-2000)

IPC programs supported programs for basketball, canoeing, cycling, hockey, rowing, men’s soccer, swimming, track and field and water polo, women’s football, baseball and softball. OAP funds were used to employ elite coaches. A number of ITC programs were cut following the election in 1998.

High- Performance Management – $8,250,111 (1994-2000)

OAP provided funding to assist with the employment of high-performance managers in most Olympic sports. Their role was to coordinate the national sporting organisation’s high-performance program plan that was to be the blueprint for success at the 2000 Olympics. They worked closely with national coaches to ensure that the full range of OAP services is being utilised by the elite athletes.

Direct Athlete Support (DAS)- $ 7,710,804 (1994-2000)

The OAP provided DAS funding to athletes to assist them with the costs associated with participating in elite sport. All OAP athletes were eligible for this assistance valued between ($2,000 and $15,000) a year and this was related to a sports categorisation. An income test did apply and athletes with an income greater than $50,000 a year were ineligible to receive DAS support.

National Training Camps – $11,376,067 (1994-20000)

OAP athletes were provided access to AIS training centres and professional services in Canberra and Thredbo (altitude) as well as other Australian based or international venues. These camps were primarily for the final preparation for major events in Australia and overseas.

Athlete Development Funding – AIS scholarship support and national program coaches -$12,610,954 (1994-2000)

Several AIS programs were established as a result of OAP funding. These sports employed well credential international coaches.

Other OAP – career/education, sport research, information services $10,957,114

OAP provided funding for research in three key research – applied research, performance monitoring and equipment and technology development. Examples of projects that were funded in this area included the development of a “Superbike” frame, Body cooling jackets, altitude simulation studies, immune function studies, performance enhancing diets, markers of overtraining and recovery, psychological stressors in elite competition and numerous sport specific competition analysis systems.

Talent Search was implemented by 23 sports by 1998-1999. OAP Program employed Talent Search state coordinators.

The Athlete Career and Education (ACE) was funded to assist OAP athletes to effectively balance their sport, education and career aspirations by providing individual case management, competency-based training, audio/visual resources and other self-educating material.

Information services included the development of Sportnet and extension of National Sport Information Centre services to coaches, sports scientists and administrators.

Paralympic Team Preparation -$5,450,000

Australian Paralympic Committee managed the distribution of funds to 18 sports.

Russian Exchange Program – $1,382,055

Agreement between ASC, AOC, and Russian Olympic Committee for the exchange of information on Russia’s high-performance programs. February 1996 visit that examined the Russian high-performance system. The Russian Exchange Program provided help in developing a prognostic assessment system that might be used for evaluating high-performance sport inputs and outputs.

Reflections

In Jim Ferguson’s book ‘More than Sunshine & Vegemite: Success the Australian Way‘, Geoff Strang who managed the OAP/PPP programs for the ASC reflected:

The OAP was the first national elite sports program that offered a fully integrated suite of high performance services, infrastructure and financial support. Initially, we had some difficulty getting the management of some national sporting bodies to understand the concept of a performance based program or the need to manage it as a discrete entity outside the normal day to day demands of management and this led to the establishment of special management committees to oversight a number of sports. These committees provided a lot of ‘hands on’ direction until such time as the sports demonstrated that they have the drive and capacity to manage themselves. The outstanding legacy of the OAP was the establishment of a national elite sports framework that has been the basis for continuing success at international level”.,

Some reflections from my viewpoint and past ASC administrators include:

- OAP/PPP significantly professionalised high-performance in Australia through increased funding for elite coaches, employment of high-performance managers and increased rigour to funding decisions.

- Majority of Olympic medals were won in Category One sports. Category Two-Three sports – archery, baseball, equestrian, diving, gymnastics (trampolining), judo, taekwondo and beach volleyball won medals and these sports helped to ensure Australia finished in the top five in the medal count.

- It was important to provide an appropriate level of funding for all Olympic and Paralympic sports as they were competing in front of their home crowd. This was seen as very important by the AOC.

- Sports science and medicine was viewd as a critical component of high-performance sport through additional resources, employment of sports science/sports medicine coordinators and critical ground-breaking research (heat, altitude, EPO etc).

- Talent identification and development through Talent Search and ITC programs highlighted the importance of this foundation in the development of Olympic sports. The outcomes of this investment were also seen through athlete performances at the 2004 and 2008 Olympics.

- AIS in Canberra played a central and critical role through the expansion of its scholarship programs, employment of highly credentialed international coaches, innovative sports science, management expertise and use of its facilities for AIS programs and national teams. Existing AIS sports programs outside Canberra – hockey (Perth), track cycling (Adelaide), diving (Brisbane) and sprint canoeing (Gold Coast) with strong medal opportunites were well supported and utilised where relevant expertise from the AIS in Canberra.

- Funding to SIS/SAS for Athlete Career and Education (ACE) and sports science/medicine services in someways was buying asherence to the national plan.

- Increased financial support for high-performance sport from the Australian Government (ASC and AIS), State Governments (SIS/SAS) and the Australian Olympic Committee.

- Paralympic athletes funding was well below that provided to Olympic athletes. Following Sydney Paralympics, funding has markedly increased for Paralympic athletes and their support is now primarily through national sports organisations than Paralympics Australia.

- Funding after Sydney Olympics and Paralympics had a brief pause – this resulted in many national sports organisations loosing experienced staff.

- Post the Sydney Games there has been a move to devolve more high-performance management to national sports organisations. I have seen commentary around several sports not being equipped to manage this responsibility due to their small participation base and limited administrative capacity and the decline in ASC close supervision.

- During OAP, the ASC became more involved in national sports organisations that had difficulties in managing their high-performance programs. But across the entire sport portfolio, ASC/AIS staff developed an intimate knowledge of each sports’ domestic and international operating environments and established close working relationships with key NSO personnel.

- There was public accountability of how OAP funds were distributed to NSO’s. ASC annual reports provided detailed breakdown of OAP funding to NSO’s. These days ASC annual reports only breakdown funding by high-performance, participation and other.

- The critical mass of highly talented athletes at the AIS in Canberra attracted some of the best coaches and scientific minds to create a hotspot of applied performance innovation.

Appendix 1

Sources:

- Australian Sports Commission Annual Reports 1994/95 to 2000/19 – PDF’s available through Clearinghouse for Sport

- Olympic Athlete Program 1994 – PDF available through the Clearinghouse for Sport

- Gold Medal Plan Australian Olympic Committee – PDF available through the Clearinghouse for Sport

- Keating Government Cabinet Documents 1994

- Olympic Athlete Program 2000 website – available through Wayback Machine

- 1998 OAP Review Media Release – available through Wayback Machine

- Jim Ferguson. More than Sunshine & Vegemite : Success the Australian Way. Sydney, Halstead Press, 2007 (OAP covered pages 69-75)

Thanks to several former senior ASC staff who were significantly involved in the management of the OAP/PPP for feedback and comments on this article.

Note for academics – OAP/PPP detailed evaluation would be an ideal PhD research program. There has been no detailed review undertaken by the ASC or other organisations.

4 responses to “Revisiting Olympic Athlete Program & Paralympic Preparation Program (1994-2000)”

[…] – I have a new article reflecting on the ground breaking Olympic Athlete Program (1994-2000) https://australiansportreflections.wordpress.com/2021/03/10/revisiting-olympic-athlete-program-paral… Read […]

[…] to review AIS funding principles and programs as Australia needs to develop a plan similar to the Olympic and Paralympic Athlete Program (1994-2000) as Brisbane and South East Queensland hosts the 2032 Games. The 2000 plan spread the funding to […]

[…] Blood, Revisiting Olympic Athlete Program & Paralympic Preparation Program (1994-2000), 10 March […]

[…] Government implemented a six year $140 million high performance funding plan known as the Olympic and Paralympic Preparation Program. This long-term plan significantly improved high-performance planning and led to Australia’s best […]